Corinne Teed

Multimedia artist, activist and professor of art

Moorhead, MN

Multimedia artist, activist and professor of art

Moorhead, MN

"Corinne Teed is a research-based multimedia artist who works in printmaking, installation, time-based media and social practice. She is the professor in Printmaking at the School of Visual Arts at Minnesota State University Moorhead and teaches printmaking, sequential art and drawing courses. Her research interests include queer theory, ecology, critical animal studies and postcolonialism. Teed has attended artist residencies at ACRE, Signal Fire, AS220 and Virginia Center for Creative Arts, while her work has been exhibited in the U.S. and abroad. Teed received a BA in Development Studies from Brown University in 2002 and an MFA in Printmaking and Intermedia from University of Iowa in 2015."

L: What is your background in collectives and collaboration?

C: Before I went to grad school for visual art I worked as a community organizer and I was part of this worker-owned collective for five years. It was called "Connections Co-op" and we were a translation, interpretation and education collective. We did translation work both professionally and as volunteers. Professionally we would be translators at city council meetings and volunteer-wise we would translate for folks at their immigration appointments. We also did a lot of education. We'd facilitate community-based workshops and training people on facilitating workshops, etc. For me that feeds into my pedagogical practice because I am accustomed to learning environments where participatory pedagogy is essential because you're trying to build broad community leadership. The notion of the facilitator as the authority really makes no sense in that context. I think an academic environment can be complicated because I'm still giving students a grade. So I'm not totally saying, "Hey, we’re all on the same level here." But I do think helping students develop a sense of leadership and ownership in the classroom and in their work is really important. As you know, I'm a Marxist and I am pretty anti-capitalist in my personal worldview. And one of the things that's really challenging to me about the current space in which I teach is it that it does promote capitalist ethics of individual success and investment in your own personal career. I think collaborative projects for undergraduates feels like community-building because it's one way of practicing being in community. We live in a culture that promotes individualization and isolation. Figuring out ways that students get in the habit of being more collaborative or engaging outside of the classroom, like having their art practice engage outside of the classroom or outside of the studio feels like an important act. I'm a young educator, in terms of teaching in academic environments so I'm still figuring out how to do that in a way that feels right to me. I wouldn't consider myself an expert on this in any way but I'm working on it!

L: Well, it's still good to talk to you about it though because there are people out there who totally agree with us on how individual success isn't the most important thing. But yeah, it's still hard to find all the academic research so I was interested in finding out your personal, real-world experience with this. Could you talk about some specific projects where you had your students collaborate?

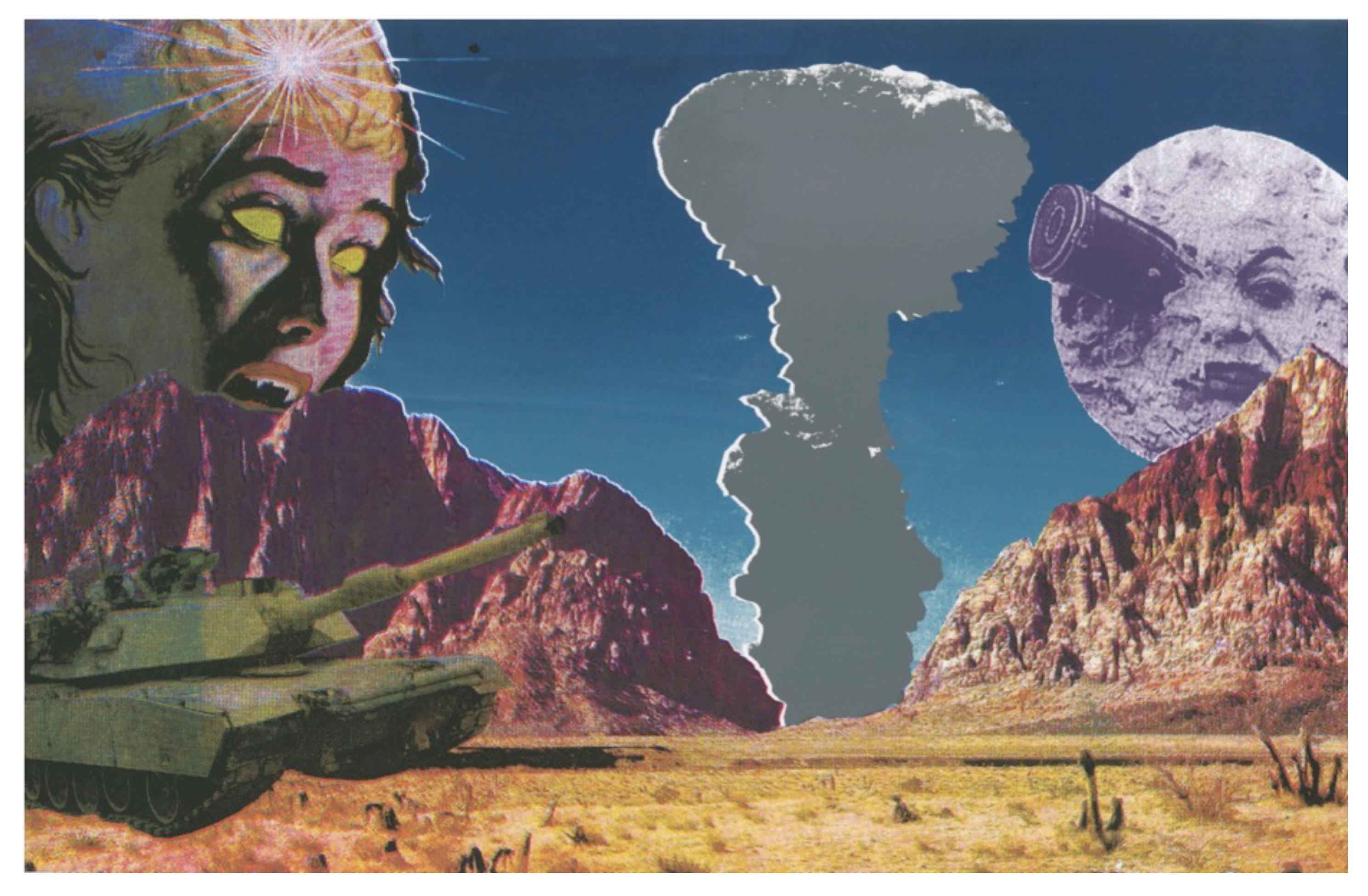

C: I can tell you a few different projects. My first group project that I designed is called the "CMYK Utopias/Dystopias" project. This was in the context of an Introduction to Printmaking class and wanting to teach the CMYK screenprinting process. In the past, I had taught it and I found that there were - dependent on their background with digital applications - some students who really had a hard time with it. I decided it would be better to do it as a quick group project. Quick because the printing process has to be a lot quicker when you have three people working on it. But also that they would be mutually supportive and learning these [social] skills. I gave a presentation on speculative worlds and definitions of utopia and dystopia and notions of world-building - what it means to define a world that's different than our own and maybe follows different rules. We looked at some examples in contemporary art. In groups, they then defined their collective world or the rules of their collective world. So the characteristics of their utopia/dystopia, and then they each went and found images that represented this world. They came back together and made a collaborative digital collage... So that's just one example of a group project.

L: What is your background in collectives and collaboration?

C: Before I went to grad school for visual art I worked as a community organizer and I was part of this worker-owned collective for five years. It was called "Connections Co-op" and we were a translation, interpretation and education collective. We did translation work both professionally and as volunteers. Professionally we would be translators at city council meetings and volunteer-wise we would translate for folks at their immigration appointments. We also did a lot of education. We'd facilitate community-based workshops and training people on facilitating workshops, etc. For me that feeds into my pedagogical practice because I am accustomed to learning environments where participatory pedagogy is essential because you're trying to build broad community leadership. The notion of the facilitator as the authority really makes no sense in that context. I think an academic environment can be complicated because I'm still giving students a grade. So I'm not totally saying, "Hey, we’re all on the same level here." But I do think helping students develop a sense of leadership and ownership in the classroom and in their work is really important. As you know, I'm a Marxist and I am pretty anti-capitalist in my personal worldview. And one of the things that's really challenging to me about the current space in which I teach is it that it does promote capitalist ethics of individual success and investment in your own personal career. I think collaborative projects for undergraduates feels like community-building because it's one way of practicing being in community. We live in a culture that promotes individualization and isolation. Figuring out ways that students get in the habit of being more collaborative or engaging outside of the classroom, like having their art practice engage outside of the classroom or outside of the studio feels like an important act. I'm a young educator, in terms of teaching in academic environments so I'm still figuring out how to do that in a way that feels right to me. I wouldn't consider myself an expert on this in any way but I'm working on it!

L: Well, it's still good to talk to you about it though because there are people out there who totally agree with us on how individual success isn't the most important thing. But yeah, it's still hard to find all the academic research so I was interested in finding out your personal, real-world experience with this. Could you talk about some specific projects where you had your students collaborate?

C: I can tell you a few different projects. My first group project that I designed is called the "CMYK Utopias/Dystopias" project. This was in the context of an Introduction to Printmaking class and wanting to teach the CMYK screenprinting process. In the past, I had taught it and I found that there were - dependent on their background with digital applications - some students who really had a hard time with it. I decided it would be better to do it as a quick group project. Quick because the printing process has to be a lot quicker when you have three people working on it. But also that they would be mutually supportive and learning these [social] skills. I gave a presentation on speculative worlds and definitions of utopia and dystopia and notions of world-building - what it means to define a world that's different than our own and maybe follows different rules. We looked at some examples in contemporary art. In groups, they then defined their collective world or the rules of their collective world. So the characteristics of their utopia/dystopia, and then they each went and found images that represented this world. They came back together and made a collaborative digital collage... So that's just one example of a group project.

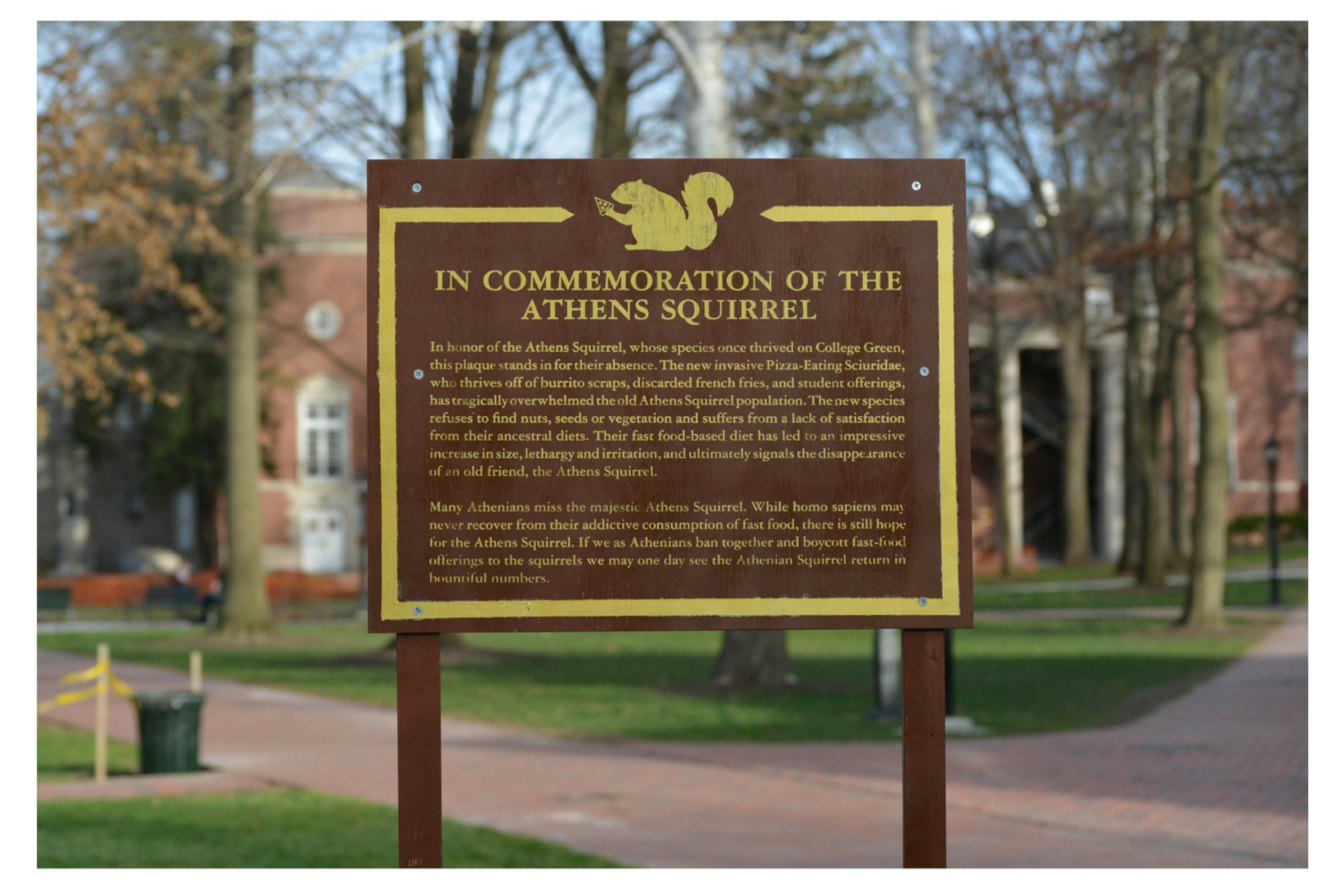

Another project I taught was I got from Sarah Kanouse who was an intermedia professor at University of Iowa and she's at Northeastern now. In my Art & Ecology class that I taught at Ohio University I had [my students] do a small group project. They started by going on what's called a Dérive which is a Situationist practice of walking without purpose, walking in response to your environment and not trying to get somewhere and instead trying to respond to where you are. So they got into small groups and they each took turns leading the group in this walk - it was a silent walk - and they had to observe - be in observation mode - of their environment. This was after doing lots of readings about ecology and looking at a lot of ecologically oriented art. They then came back together and they wrote about their experience and eventually after a group dialogue they made a small group public art project that was in response to something that they noticed in the environment. So, some examples of projects that came out - one group noticed how different the squirrels on campus were than other squirrels and they saw lots of squirrels eating trash strewn about, pizza slices, whatever. And they also noticed the formal signs that the University had out and so they made a fake Ohio University sign. They made it look much like the formal signs that were around campus. And it was, "In memory of the absent squirrel. (The native species has been replaced by the pizza eating squirdé)." [Louise laughs] So, it was talking about this messed up relationship between humans and animals. Anyway, that project was really funny.

L: [Still laughing] Did they install it too - on campus?

C: Oh, they installed it on the main green of campus. Yes.

L: HA!

C: They had to get around eight signatures on campus to do a public art installation. But they did it!

L: [Still laughing] Did they install it too - on campus?

C: Oh, they installed it on the main green of campus. Yes.

L: HA!

C: They had to get around eight signatures on campus to do a public art installation. But they did it!

L: And then what about the prairie grass project?

C: Oh, yeah! So this semester, in my Intermediate Printmaking class of five students, I had them do collaborative public art project. So, first I set up an agreement with the Plains Art Museum which is the art museum in Fargo... that we would have this public space in the museum to do an installation. They were doing a month of printmaking activities so I kind of jumped on for the opportunity for my students to do something big in the museum, because I think that kind of thing is an incredible opportunity for students and also, allowed an opportunity for me and other professors to collaborate with the museum. The museum has a pollinator garden that an artist had slowly been building... all around the museum, so there was already an ecologically themed permanent installation... and I suggested to the museum that would my class could do was something related to tall-grass prairie, which is the native habitat here. They were totally excited about it. I wrote up a proposal. When class started, the first day of class I met these students - and I'm new here so I didn't know these students at all - and I explained the project to them. I said, "I'm not going to require you to do this because this is a huge project. And it's a real opportunity for you to make something that you would never be able to make on your own and to have a piece up at the museum. But it's only going to work if you guys really want to do it and you're excited about it." And so I gave them an option to say no to the project. And I was like, "Every one of you has to say yes. Three of you can't make a decision for five. You all have to be into it! I'm going to go around the room right now and I'm going to look into each of your eyes and I'm gonna ask if you want to do this project. And I'm gonna ask you to reach down deep inside of yourself and tell me really of you want to do it or don't want to do it". And they all looked me in the eye and said yes. [Louise laughs] The reason I did that is because doing a project like that - that's a lot to ask - there's a lot of pressure in it, getting to publicly install in the museum, you know. If they didn't want to do it, I wasn't going to drag them through the project so it had to be an act of love, not of requirement.

So they were excited about it and we went on a field trip with this really wonderful biology professor here who does a lot of tall grass prairie restoration projects with her students. About twenty miles out of town, there's what's called the Minnesota State University Moorhead Regional Science Center and that's where they do all the tall grass prairie habitat restoration. She took us through the prairie and talked a lot about what was at stake in restoration and preservation and some other challenges, and history. For the next class [period] I had students write a response to that trip asking very specific questions and the things that stood out most to them, teachings they remembered, etc. We then had a dialogue about what story they wanted to tell about the threatened habitat of the tall grass prairie. That was one of the moments when I was the most impressed with them. They had really strong visions for what they wanted this installation to do. One of them said, "I think it's really important that we include invasive species in the installation because that's a reality of what we saw and what they're constantly fighting against". Another felt like it was really important that the roots were in the installation, and if we were going to include invasive species showing the difference between the shallow roots of these invasive species and these deep-rooted prairie plants. Another student really wanted to have traces of mammals on the land. And then the thing for me that had to be in the installation was the inclusion of indigenous human communities in the landscape. Often the preservation of habitat is framed in such a way that human behavior inhibits prairie restoration, and that a protected native habitat doesn't include humans, right? And this is problematic because of Native populations and the fact that Natives actually lived in concert with the ecosystems around them and often were essential members of a functioning ecological community. So, a great example is the relationship between indigenous communities and sweet grass. They’ve found is that the consistent harvesting of sweet grass, which is used not only for baskets but is also a spiritual plant to many Native communities across the country -- the picking of sweet grass is essential to the survival of sweet grass, and when its not consistently harvested, sweet grass does not thrive. That actual harvesting is what helped sweet grass survive. The way that western science has often viewed human ecological relationships with other species is that we're always bad for other species. And that's a very Western [notion]. So for me, it felt really important to include the human element too. My contribution to the installation was to include a birch bark basket full of sweet grass which is the traditional basket of the Ojibwe people. But sweet grass is important to the Lakota, Dakota and other Anishanabe people that are native to tallgrass prairie.

We all had things that we were like, "this story has to be told", you know? This was a screenprint wheat paste project, so we moved into a conversation about what were the must haves of the installation. We made a list and then miraculously, when we went around to talk about who wanted to make what, all five of those students wanted to do different things. One student wanted to do grasses, one student wanted to do bees and the roots, and another said they wanted to do wildflowers; the other wanted to make all the animals. So, it was kind of amazing how seamless that part was. Another incredible part as a teacher who’s taught group projects was that all of them did a really wonderful job. None of them slacked and they were all really invested. We collectively planned how many copies we needed for the installation - it was all a guess. Once we had everything printed we went over to install in the museum. And the installation process was we placed things on the wall and got initial composition up and walked around and edited it for about an hour before we started wheat pasting.

C: Oh, yeah! So this semester, in my Intermediate Printmaking class of five students, I had them do collaborative public art project. So, first I set up an agreement with the Plains Art Museum which is the art museum in Fargo... that we would have this public space in the museum to do an installation. They were doing a month of printmaking activities so I kind of jumped on for the opportunity for my students to do something big in the museum, because I think that kind of thing is an incredible opportunity for students and also, allowed an opportunity for me and other professors to collaborate with the museum. The museum has a pollinator garden that an artist had slowly been building... all around the museum, so there was already an ecologically themed permanent installation... and I suggested to the museum that would my class could do was something related to tall-grass prairie, which is the native habitat here. They were totally excited about it. I wrote up a proposal. When class started, the first day of class I met these students - and I'm new here so I didn't know these students at all - and I explained the project to them. I said, "I'm not going to require you to do this because this is a huge project. And it's a real opportunity for you to make something that you would never be able to make on your own and to have a piece up at the museum. But it's only going to work if you guys really want to do it and you're excited about it." And so I gave them an option to say no to the project. And I was like, "Every one of you has to say yes. Three of you can't make a decision for five. You all have to be into it! I'm going to go around the room right now and I'm going to look into each of your eyes and I'm gonna ask if you want to do this project. And I'm gonna ask you to reach down deep inside of yourself and tell me really of you want to do it or don't want to do it". And they all looked me in the eye and said yes. [Louise laughs] The reason I did that is because doing a project like that - that's a lot to ask - there's a lot of pressure in it, getting to publicly install in the museum, you know. If they didn't want to do it, I wasn't going to drag them through the project so it had to be an act of love, not of requirement.

So they were excited about it and we went on a field trip with this really wonderful biology professor here who does a lot of tall grass prairie restoration projects with her students. About twenty miles out of town, there's what's called the Minnesota State University Moorhead Regional Science Center and that's where they do all the tall grass prairie habitat restoration. She took us through the prairie and talked a lot about what was at stake in restoration and preservation and some other challenges, and history. For the next class [period] I had students write a response to that trip asking very specific questions and the things that stood out most to them, teachings they remembered, etc. We then had a dialogue about what story they wanted to tell about the threatened habitat of the tall grass prairie. That was one of the moments when I was the most impressed with them. They had really strong visions for what they wanted this installation to do. One of them said, "I think it's really important that we include invasive species in the installation because that's a reality of what we saw and what they're constantly fighting against". Another felt like it was really important that the roots were in the installation, and if we were going to include invasive species showing the difference between the shallow roots of these invasive species and these deep-rooted prairie plants. Another student really wanted to have traces of mammals on the land. And then the thing for me that had to be in the installation was the inclusion of indigenous human communities in the landscape. Often the preservation of habitat is framed in such a way that human behavior inhibits prairie restoration, and that a protected native habitat doesn't include humans, right? And this is problematic because of Native populations and the fact that Natives actually lived in concert with the ecosystems around them and often were essential members of a functioning ecological community. So, a great example is the relationship between indigenous communities and sweet grass. They’ve found is that the consistent harvesting of sweet grass, which is used not only for baskets but is also a spiritual plant to many Native communities across the country -- the picking of sweet grass is essential to the survival of sweet grass, and when its not consistently harvested, sweet grass does not thrive. That actual harvesting is what helped sweet grass survive. The way that western science has often viewed human ecological relationships with other species is that we're always bad for other species. And that's a very Western [notion]. So for me, it felt really important to include the human element too. My contribution to the installation was to include a birch bark basket full of sweet grass which is the traditional basket of the Ojibwe people. But sweet grass is important to the Lakota, Dakota and other Anishanabe people that are native to tallgrass prairie.

We all had things that we were like, "this story has to be told", you know? This was a screenprint wheat paste project, so we moved into a conversation about what were the must haves of the installation. We made a list and then miraculously, when we went around to talk about who wanted to make what, all five of those students wanted to do different things. One student wanted to do grasses, one student wanted to do bees and the roots, and another said they wanted to do wildflowers; the other wanted to make all the animals. So, it was kind of amazing how seamless that part was. Another incredible part as a teacher who’s taught group projects was that all of them did a really wonderful job. None of them slacked and they were all really invested. We collectively planned how many copies we needed for the installation - it was all a guess. Once we had everything printed we went over to install in the museum. And the installation process was we placed things on the wall and got initial composition up and walked around and edited it for about an hour before we started wheat pasting.

It took a while to get it up but it's beautiful. They did an incredible job. It's really wonderful to see students be super proud of their work and I think it's an instance where none of them would have been able to do something like that on their own. I wouldn't have been able to make something like that on my own, you know? It was a really beautiful piece of collaboration where the alchemy of the people working together made the work undeniably better. And the museum staff who will look at it every day were so taken with it. They originally were going to take it down in December and immediately started planning to keep in up for longer. It looks like they will keep it installed for at least a year now.

L: The next question is why do you think artists form communities?

C: I think that artists are inherently involved in relational work. The majority of us make work because we want to communicate with other people. We have a story we want to tell or a feeling we want to provoke in someone. What is art without an audience? What is art without communicating to someone? It makes sense to me that as people involved in inherently relational work that we would also be people interested in communities. And there are different artists. There's definitely artists who have a super solo studio practice that aren't interested in working with others and that's part of how they are in the world but I think many of us are interested in not only mutual support but in interdependent engagement. Meaning that we are working on projects together or building each other up. It's so interesting to talk about this right now because as somebody who's moved to a new place I don't have it right now and it feels difficult for me. Given the current political climate, I feel like I need a community to come back to that I'm talking about what does it mean to be an artist and professor in the state of the world right now. You know? I have that individual connection to many people but I don't have that in a collective sense. I think that's a question I want to solve right now.

L: How does collaboration benefit the individual artist?

C: That's funny because it's bringing the notion of collaboration back into the benefit of the individual. But hands down, seeing how other people work and make decisions. And then for me, collaboration is so much about alchemy. I may have a certain way I think things should be done and then another artist I'm collaborating with thinks there's another way things should be done. And we debate about it! And maybe the way that the other artist thinks is actually a better idea. Or maybe I have the first idea, and then they riff off it and I riff that and eventually we get to this better outcome because together we're creating something. When I was in Sarah Kanouse's Ecology and Art class we did the same project where we walk on this dérive around the Studio Art building at the University of Iowa and groups made projects in response to their environment. And my group decided to do a memorial to beavers that have been killed when they drained the pond next to the building, because the beavers had started blocking the drainage pipes. They decided to drain the pond because they were worried that the beavers were going to make it flood, so then the beavers tried to find a new home and they all got hit on highway 6. It was pretty awful and many of us who were in the building loved those beavers. I would watch the beavers from across the pond all the time at lunch. [Louise laughs]. So we made this memorial beaver lodge, and there were a lot of questions about how we were going to make this memorial. What would it look like? What if we made a sculpture of a beaver? No, what if we made a lodge that people could gather together in? Would it be inside the building or would it be on-site in the old pond?

C: I think that artists are inherently involved in relational work. The majority of us make work because we want to communicate with other people. We have a story we want to tell or a feeling we want to provoke in someone. What is art without an audience? What is art without communicating to someone? It makes sense to me that as people involved in inherently relational work that we would also be people interested in communities. And there are different artists. There's definitely artists who have a super solo studio practice that aren't interested in working with others and that's part of how they are in the world but I think many of us are interested in not only mutual support but in interdependent engagement. Meaning that we are working on projects together or building each other up. It's so interesting to talk about this right now because as somebody who's moved to a new place I don't have it right now and it feels difficult for me. Given the current political climate, I feel like I need a community to come back to that I'm talking about what does it mean to be an artist and professor in the state of the world right now. You know? I have that individual connection to many people but I don't have that in a collective sense. I think that's a question I want to solve right now.

L: How does collaboration benefit the individual artist?

C: That's funny because it's bringing the notion of collaboration back into the benefit of the individual. But hands down, seeing how other people work and make decisions. And then for me, collaboration is so much about alchemy. I may have a certain way I think things should be done and then another artist I'm collaborating with thinks there's another way things should be done. And we debate about it! And maybe the way that the other artist thinks is actually a better idea. Or maybe I have the first idea, and then they riff off it and I riff that and eventually we get to this better outcome because together we're creating something. When I was in Sarah Kanouse's Ecology and Art class we did the same project where we walk on this dérive around the Studio Art building at the University of Iowa and groups made projects in response to their environment. And my group decided to do a memorial to beavers that have been killed when they drained the pond next to the building, because the beavers had started blocking the drainage pipes. They decided to drain the pond because they were worried that the beavers were going to make it flood, so then the beavers tried to find a new home and they all got hit on highway 6. It was pretty awful and many of us who were in the building loved those beavers. I would watch the beavers from across the pond all the time at lunch. [Louise laughs]. So we made this memorial beaver lodge, and there were a lot of questions about how we were going to make this memorial. What would it look like? What if we made a sculpture of a beaver? No, what if we made a lodge that people could gather together in? Would it be inside the building or would it be on-site in the old pond?

All these questions came together and I think the way we solved them was pretty free. There were three of us in the group and two of us were very headstrong. So the third one who wasn't as headstrong... was kind of like the deciding voice and it worked out great. The other headstrong person, we're still friends - it's not like we were fighting. I think that debate and dialogue is really essential to bettering a project. You learn your ways of working and then you also make better work. I often I feel like the alchemy of people coming together and talking through projects can really make incredible things happen.

L: So building off that, what do you think constitutes a healthy collaboration and what would undermine it?

C: I think that a healthy collaboration means all people's voices are considered and important to the project. And people have different ways of participating so it doesn't always look the same. I think the fact that everybody adding input in whatever way possible or adding labor in whatever way is possible. When things are complicated in collaborations is when one person takes over because they think they can do it better. And I've definitely had that in class collaborations a couple of times.

L: Ha, the ego.

C: Yes, totally. Or just not trusting each other. Trust feels very important.

C: I think that a healthy collaboration means all people's voices are considered and important to the project. And people have different ways of participating so it doesn't always look the same. I think the fact that everybody adding input in whatever way possible or adding labor in whatever way is possible. When things are complicated in collaborations is when one person takes over because they think they can do it better. And I've definitely had that in class collaborations a couple of times.

L: Ha, the ego.

C: Yes, totally. Or just not trusting each other. Trust feels very important.